Setting the Vent I: Ventilation

This is the ninth video in our Pulmonary and Ventilator Mechanics Chalk Talk Series, where our goals are to learn how a ventilator works, and how to work a ventilator. In this talk, look at the nuts and bolts of treating hypercarbia in a ventilated patient. Using an example patient, we review different strategies to increase minute ventilation, and the trade-offs and complications that must be balanced in each.

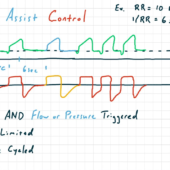

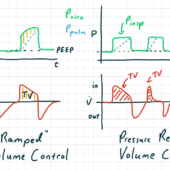

Volume Control

We start with an example patient who was intubated for airway protection and now is being ventilated in volume control mode. From this baseline, we'll look at two strategies for increasing minute ventilation. Although we are looking at volume control mode, the general principles apply to any mode that uses flow-limited breaths. Our example patient is an average adult intubated for airway protection, with an arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure of 60mmHg. Our goal is to decrease the PaCO2 to 40mmHg.

VC: ↑ Resp Rate

Strategy #1 is to increase the respiratory rate. Because our goal PaCO2 is 2/3 of our current PaCO2, and the alveolar minute ventilation is proportional to the respiratory rate, we will increase the respiratory rate by 3/2, or 150%. In this example, that means increasing the respiratory rate from 12 to 18 breaths per minute.

However, as we draw out the pressure- and flow-time curves after the respiratory rate adjustment, the first complication or trade-off in increasing ventilation becomes evident: auto-PEEP. Because we increased respiratory rate with a fixed I:E ratio, our new expiratory time is insufficient for exhalation of the same tidal volume. To prevent this, we should have decreased our I:E ratio when we increased respiratory rate.

VC: ↑ Tidal Volume

Strategy #2 is to increase the tidal volume. Because minute ventilation is proportional to the tidal volume less the dead space, it's necessary to estimate the alveolar volume. We find our target tidal volume by increasing alveolar volume by 150% and then adding dead space back in.

Drawing the pressure- and flow-time graphs after increasing tidal volume, we see the second trade-off in increasing ventilation: increasing plateau pressure. Because plateau pressure depends only on tidal volume and pulmonary compliance, an increase in tidal volume will always cause an increase in plateau pressure. This increases risk of ventilator induced lung injury, which we will discuss more in the next talk.

Pressure Control

Next, we'll look at the same patient in pressure control mode. These strategies apply to any pressure-limited ventilator mode. In pressure control, the set inspiratory pressure Pinsp is, by convention, relative to the positive end expiratory pressure, PEEP.

PC: ↑ Resp Rate

Just like in volume control mode, Strategy #1 is to increase the respiratory rate. Using the same calculation as in volume control mode, we increase the respiratory rate to 18 breaths per minute and draw the resulting pressure- and flow-time curves.

In this case, we realize that the decreased inspiratory time -- a consequence of the increase in respiratory rate -- have resulted in truncated inspiration. Our third trade-off, truncated inspiration results in pressure-limited breaths with insufficient inspiratory time. Though not directly harmful to the patient, it results in unexpectedly low minute ventilation. In this example, our minute alveolar ventilation has actually decreased by 5%, resulting in worsening hypercapnia.

PC: ↑ Insp Pressure

Strategy #2 is to increase the inspiratory pressure. The exact inspiratory pressure required is not straightforward to predict. In reality, you generally adjust the inspiratory pressure slowly to hit a target tidal volume. This strategy works well, with only the predictable tradeoff of increasing pulmonary pressure.

In this lecture, we covered the main strategies to increase ventilation in volume and pressure control modes. Next time, we'll take a look at optimizing oxygenation.

Comments

This post currently has no responses.